When do unexploded bombs in the sea move?

The bottom of the North Sea is still littered with unexploded bombs from the Second World War. Electricity transmission system operator TenneT wants to know what causes the bombs to move, so they can avoid risks to humans. Deltares has joined the research team, using the Delta Flume test facility in Delft. Peter Menzel, scientific consultant at TenneT, explains.

Peter Menzel

Peter is currently an adviser at TenneT, working on converting scientific results to applicable solutions in the offshore industry.

Previously, Peter worked in the Ocean Engineering department at the University of Rostock. His research focused on ocean engineering, naval architecture, and fluid dynamics.

What’s the unexploded ordnance (UXO), or unexploded bombs, project about?

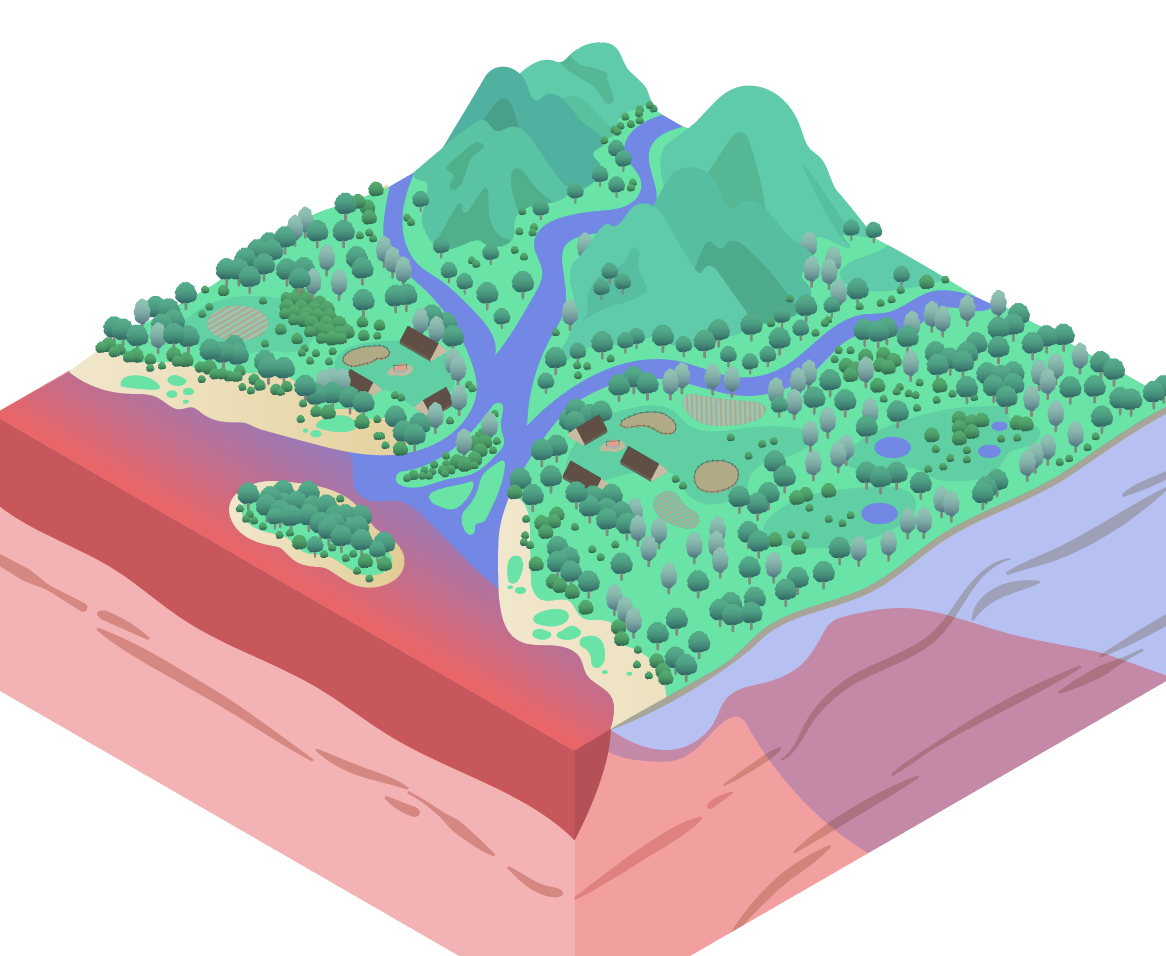

“TenneT is responsible for transporting offshore-generated power to the shore. We manage the offshore grid connections which connect the offshore platforms via cables to the substations on land. If we discover unexploded bombs on our cable route, we either go around them or remove them. The question is: what happens when we go back to carry out repairs? Could the objects along our cable route move? Waves can mobilise and move an object, but this depends on the size of the waves, the depth, weight and size of the object. We developed a numerical model we want to validate in experiments together with Deltares in their flume tank. We have to know how big the risk is and how to eliminate any risk to our people.”

How many bombs are still in the North Sea?

“There are no data about this in the Netherlands, but according to publications here in Germany there are at least 1.6 million tonnes of unexploded ordnances at the bottom of the German sector of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.”

We need scientific proof for our models and risk assessments

Peter Menzel - Advisor at TenneT

Have there been any accidents?

“I’ve never heard of any fatal incidents in the history of offshore oil and gas platforms, renewable energy installations or communication cables. A few times fishing vessels have accidentally pulled unexploded bombs up onto their deck. It’s a big problem for the environment, but the risk is extremely small for TenneT. Most bombs are clustered in known dump sites, and we intentionally avoid those. The majority of objects we come across are rubbish like bicycles or containers. People have only recently started to consider this risk, since more work is being done at sea due to the construction of offshore wind farms.”

Bombs from the Second World War

Guido Wolters, project engineer at Deltares and involved in the project, comments: “The mobilisation of bombs from the Second World War is a serious danger for the offshore industry in Europe. By investigating their mobilisation under waves in the large Delta Flume, Deltares is helping extend and calibrate existing forecasting models that can predict bomb movements.”

How is this research being conducted?

“We asked Deltares to build three concrete and steel models of bombs. I don’t think Deltares would be happy if we put a real bomb in their flume. We generate waves, making them bigger and bigger until the object starts to move. Meanwhile we measure the water velocity and height of the waves, the position of the objects, and whether they’re moving. We need scientific proof for our models and risk assessments instead of just guesses.”